For the second installment, I spoke to two sports journalists who present quite a contrast: one American, one Brit; one 40-year veteran of tennis writing, one who got his start covering tennis just as Djoković made his push to the very top of the ATP rankings; one who now writes mostly for online sports publications, one who works for a daily newspaper. The interviews with Peter Bodo and Simon Briggs were conducted primarily with a Serbian audience in mind and published by B92. Read my earlier exchanges with Brian Phillips and Steve Tignor here.

✍✍✍

Simon Briggs became The Telegraph’s tennis correspondent in 2011 after writing about England’s national sport, cricket, for fifteen years. He played both sports in his youth, but opted for cricket “properly”—on a competitive level—and tennis only “socially,” as the two sports’ seasons overlap. Briggs began dabbling in tennis journalism while in Australia covering the start of the cricket season, being asked to send reports home when Andy Murray did especially well down under (the Scot made his first of four Aussie Open finals to date in 2010). This spring, Briggs got to meet with Djoković one on one for a Telegraph magazine cover story, an interview during which he got to know the “real Novak.”

AM: During Wimbledon, Grantland’s Louisa Thomas quoted a British journalist saying, “I’m not a tennis correspondent; I’m an Andy Murray correspondent.” I’m curious if you think that accurately describes your job?

Briggs: I have said that in the past… Yeah, that’s because of the lack of depth that we’ve had. So, when we have the Konta story or something, it’s a nice break from covering Andy. He keeps us going as journalists, because if there wasn’t Andy—I don’t know how many of us there are, maybe 10-12, in that alley—we certainly wouldn’t exist in the numbers that we do. There wouldn’t be anything else to write about.

AM: Since tennis has such a long history in Britain, why don’t the big British newspapers cover the sport as whole?

Briggs: I think it’s unfair to say we don’t—it’s a slight exaggeration. The tabloids do sometimes withdraw from events when Andy goes out, so that is proper “Andy Murray correspondent,” whereas The Telegraph, The Times, and The Guardian never do that because they take the other guys seriously. But, if Andy’s playing on a given day, then he’s the story. Unless one of the “Big Three” goes out—and he has a routine victory—that’s the only situation in which he wouldn’t be the story.

AM: To what degree do you think the focus on Murray shapes, for instance, coverage of Djoković?

Briggs: Yes, a little bit. But I think people just don’t “get” Novak the way they got Roger and Rafa. I wrote in that Telegraph magazine story that he’s in a unique position in the history of the sport to have become the guy who inherits the mantle of “top man” from two such charismatic players—they’re both phenomenons whose game style and physical appearance and marketing created a perfect storm. They’re just absolute freak events, those two. So, I think it’s tough for him to come behind them.

There’s a big problem with his game style, for one thing, in a sport which is very aesthetic. His game style isn’t pretty. He’s not a “looker” as a player; he’s a player you admire, for sure. Anyone who doesn’t admire him is not a true tennis fan—you can’t not admire and respect that guy. But it’s very tough for him in that sense.

Then, in the UK, the viewing figures (that Sky Sports record for their matches), which is the best indication, put him at fourth out of the Big Four by quite a long way. So, even though he’s been the best player in the world since I started doing this, he still isn’t anywhere near the others in terms of popularity.

AM: I’ve seen Federer referred to as an “honorary Brit.” Do you think that’s mostly because of his success at Wimbledon or also because the way he carries himself—with gentlemanly restraint, and so on—is sympathetic to the British public?

Briggs: I wouldn’t have thought that the Roger-Rafa split is so different in Britain compared to everywhere else, but maybe the Wimbledon factor means that it is. But when you’re a nation of introverts, you sometimes admire people who are out there with their emotions because that’s what most introverts really want to express.

AM: With reference to Novak’s unique position historically, do you think a player with a different style or personality might have been received more warmly by fans or media? Or would anyone face similar challenges?

Briggs: Any player who doesn’t have an absolute lorry-load of charisma. Let’s say that Kyrgios had come up behind Roger and Rafa and been the third wheel, then he would be huge because he’s just got that marketability, the “X factor” which those two have. Andy’s got a bit more weirdness about him that doesn’t apply to Novak. His game style’s quirkier and he’s more unhinged—more likely to melt down. Whereas with Novak, his very grindingness may make people take him for granted a little bit.

AM: What do you think of the Murray-Djoković rivalry? It’s been fairly lopsided recently— until Andy’s win in Montreal, Novak had won eight matches in a row.

Briggs: I think we always painted it, maybe unfairly, as an “even-Steven” business until the moment when Andy went into his back-surgery recession (after September 2013). Maybe I’m biased… In 2011, he got stuffed by Novak in Australia—that was the moment we thought, “Oooh, crickey! There seems to be a gap emerging.” Before that, it hadn’t been that big. I mean, Novak had won his first major and Andy hadn’t, right? But we all said, “Well, Andy’s always had to play Roger [in finals] and Novak got to play Tsonga.” So, there was a little bit of a sense that we could make excuses for him on that front. After that, Novak didn’t win any more majors; though he won Davis Cup, that’s not a massive deal in the UK when we’re not involved.

I think Andy always felt he had Novak’s number in juniors—he was generally ahead of him, wasn’t he, when they were growing up. So, 2011 was a bit of a shock. Then, through the Lendl years, you felt that Andy had pulled it back, beating him in two finals (even though he still lost to him in Australia).

AM: But then it was another two years…

Briggs: Yes, it was after the Wimbledon final in 2013 that it completely switched into annihilation. So, it may be British bias, but our coverage always painted them as rivals on a pretty equal level with the exception of that one big blowout in Australia. That probably was the result that drove Andy, in the long run, to get Lendl into his camp and led to a couple of years of great tennis.

AM: This year, they played the Australian Open final and French Open semi-final. Then, in the lead-up to Wimbledon, I remember seeing Andy described in the British press as the biggest threat to Novak’s title defense. There was a lot of attention at the time to Novak’s medical time-outs, courtside coaching, the ball-kid incident. What do you think of that? Is some of that the tabloid influence?

Briggs: That was the Daily Mail that really took him on about the ball-girl. I think that is maybe influenced by the Murray-Djoković rivalry and by the aftermath of the play-acting row in Australia.

AM: Do you think there was “play-acting” or did that get blown out of proportion?

Briggs: In a way, we didn’t have to make that decision, because Andy said it… I was quite careful in the immediate report—there may have been one sentence trying to explain what was going on overall, but I tried to put as much of it as possible in Andy’s words and not editorialize because it’s so difficult to know what’s going on in players’ bodies. But, sure, I think the British media would have taken Andy’s side on that.

AM: But even Andy later said that it had been blown out of proportion and that he had no issue with Novak.

Briggs: Yeah, inevitably.

AM: In some February interviews, he talked about how he had allowed himself…

Briggs: …to be sucked in.

AM: Well, not necessarily to be sucked in but to lose focus—because to say “sucked in” suggests that Novak was doing something deliberate, which I don’t think is a fact. In any case, Andy seemed to back away from that position pretty significantly.

Briggs: I think our view is that there had been some gamesmanship going on, but that Andy was as culpable for not handling it. The key quote in that whole interview after the final was something like: “I’ve experienced it before, but maybe not in the final of a Grand Slam.” You could see that what he was thinking was, “I can’t believe he’s doing this to me in a Grand Slam.” My strong interpretation of that was that he was talking about behavior—because we all know that juniors, in particular, do a lot of limping around…

We disagreed on this matter of interpretation, so perhaps it’s best to leave readers with the transcript of Murray’s comments so they can read between the lines on their own.

AM: What I found odd about some of the British coverage of the match is that it gave the impression Murray was leading, when in reality the match was tied at a set-all and Murray had a single break and hold in the third before Novak came back. Do you think there’s some wishful thinking there?

Briggs: Some thought the distraction had lost him the match, whereas I didn’t think he would have won anyway. We all know how hard it is to put Novak away. There’s also just looking for a bit of drama.

AM: But not everybody wrote it up that way, which makes me wonder: how much of that drama-seeking is because they’re writing for a British audience?

Briggs: What you’ve got to remember is that tennis is a sport that is slightly odd and unique—a sport without boundaries. It sees itself as a land in which fans follow heroes who aren’t necessarily from their country. It’s not tribal in the same way as football or other team sports. So, we maybe bring a bit more of that nationalism to our coverage, possibly because we’re competing for readers with the Premier League. Whereas the Americans take an Olympian perspective, viewing the sport from a distance, we may focus more on the “blood and guts,” since tennis—lacking the physical contact of football—can seem antiseptic otherwise.

Recommended Reading:

“Different Strokes” (2015)

✍✍✍

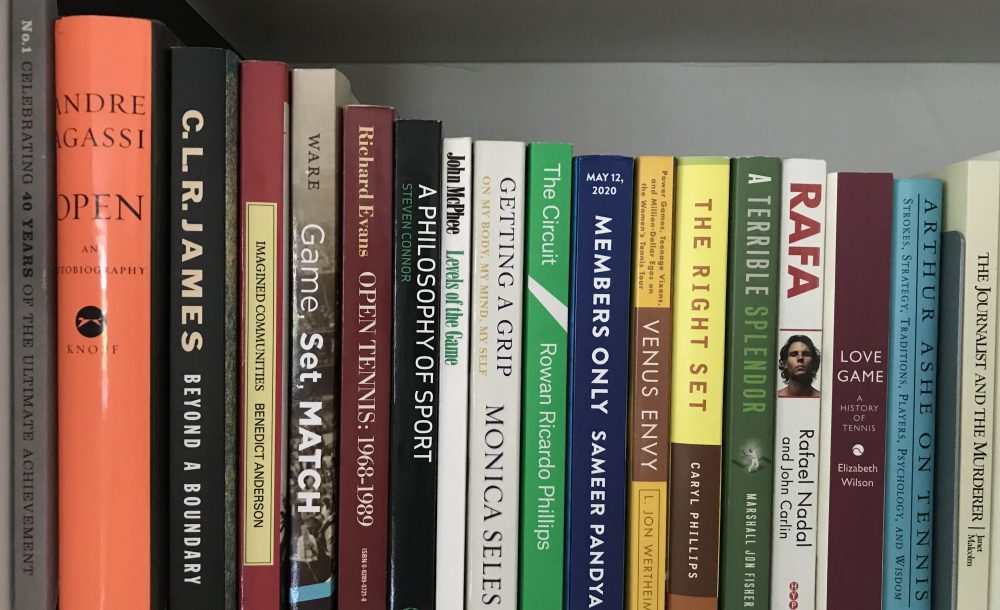

Peter Bodo has been writing about tennis for nearly forty years, beginning as a newspaper reporter during the “tennis boom” of the 1970s. He is the author of numerous books on the sport, including A Champion’s Mind, which he co-authored with Pete Sampras, and his latest, about Arthur Ashe’s historic 1975 Wimbledon win. Additionally, he’s an outdoor enthusiast who has written about hunting and fishing in both fictional and non-fictional formats. Many readers will be familiar with his writing for Tennis Magazine and its associated website, where he worked for over two decades. Currently, his columns are featured on ESPN.

AM: Do you remember when Novak first appeared on your radar?

Bodo: I remember the early controversies—the breathing issue, I think, at the French Open. But I wasn’t there that year (2005), so I really zoned in on him the year I wrote a story called “The Perfect Player.” This was at Indian Wells early on (2007) and it raises the question of the theoretically perfect player. I sat down and interviewed him for that piece. It’s kind of funny: to this day, if I write something where I criticize Djoković or not even criticize him but praise his opponent, Serbs will come out of the woodwork and attack me. Some will remind me, “You once wrote a piece…”

AM: So, your early impression was that he was a complete player?

Bodo: He was on his way. I loved the fact that he was so clean and how much rotation he had. I loved how flat his back-take was—stuff like that. He was just very economical and I thought he had all the upside in the world.

AM: What about his personality? In 2007, when he first made the final at the US Open, he was getting a lot of press for the “Djoker” side of him, the showman.

Bodo: Like most of the Eastern Europeans, he tried too hard. I’m from there, too, so I know. [Bodo’s parents were ethnic Hungarians who emigrated from Austria to the US in 1953, when he was four years old.] They try too hard, they get shat on, and they never get the respect they either deserve or feel they deserve. There’s a fair amount of snobbery toward them. They try to impress the West and are looked down upon by the West and dominated by the East (Russia). That whole region is caught in that crunch.

Of course, I’m speaking in broad generalities, but you often see the symptoms of this kind of thing. They really try to impress, they work extra hard, they try to show how smart they are: “We’re not just peasants from the middle of Europe. We can do this.”

So, you know, there was a touch of that with Novak—there still is. I always get a kick out of the way he talks like a bureaucrat—he kind of gives speeches.

AM: I noticed that his press conference answers have been getting longer and longer.

Bodo: Yes. He never says, “I don’t think that’s true, period.” There’s always a preface to his answers, a middle part, and a conclusion. On the whole, though, I think he’s been a real asset. He really wants to do the right thing. He wants to be a good citizen, a good representative of his country, and a force for good in the sport and the world.

AM: Looking back to somebody like Lendl, it seems to me that he was not only from Eastern Europe but also a particular kind of player and personality. That lent itself, in a way, to certain stereotypes. I’ve seen a number of comparisons between the two, especially regarding fans’ response to them. But I’m not sure I buy it—for one thing, because I’m skeptical of using “machine” metaphors to describe Novak.

Bodo: Right. They’re different. Lendl came from a very different and harsher situation. When Lendl got off the plane here and saw the headline “John Lennon was shot,” he asked, “Who is John Lennon?” Novak went to Germany when he was fairly young and was exposed to Western culture. He grew up in a whole different time. Their personalities are different, too. I got to know Lendl pretty well over the years. He’s got a good sense of humor, and I quite like him, but he’s a cold guy. If you were drowning, I’m not sure Lendl’s the guy you’d want passing by in a boat.

AM: You probably remember the Roddick incident from 2008. To what extent do you think something like that changes how people feel about a player or how a player acts in public? Do you attribute how much more circumspect he is now to maturity or something more strategic?

Bodo: I think it’s all of the above. He was a young guy who had a sobering experience. I’m not sure what he took away from it, but he probably got back to the locker-room and said, “I don’t want to get in these situations.” I don’t think it mattered one bit to people. It didn’t matter to me. Even somebody who booed him at that moment, I don’t think they came back the following year and thought, “There’s that Djoković who did this last year and I booed him.”

AM: Do you think it’s inevitable that any player coming after Federer and Nadal would find media and fans slow to warm to him or could you imagine his being welcomed with open arms?

Bodo: Well, there’s not that much room at the top, for one thing. So, I think it would have taken an exceptional amount of a) charisma, b) results, and c) marketability—a last name like Federer, Nadal, Johnson, or Roddick would have helped, too. It would have taken a perfect storm of user-friendly features to make that happen, which weren’t necessarily there.

AM: When you talk about marketability, you mean mainly in the West?

Bodo: Yes, of course.

AM: So, the fact that Serbia’s a tiny market is relevant. Do you think its recent history matters as much to Novak’s reception?

Bodo: Nobody here knows Serbia’s history, trust me. (Laughing.) No, I don’t think it’s that he’s from Serbia—it’s because he’s from “Where the **** is that?” That’s what it is for these people. Nobody knows.

He’s exotic. His name’s hard to pronounce, he’s got the funny hair—all that stuff sort of plays into it, even his accent, though that’s changed a lot. It never gets to the level of, you know, “He’s from that place that did this or has this history.”

AM: You don’t think there’s an anti-Serb bias to it?

Bodo: No. It’s definitely not anti-Serb—it’s anti-otherness. Anyone who believes that must think all these people read about the UN and Serbia and what NATO did. No: 99.2% of Americans have no idea about that stuff.

AM: Especially after he won Wimbledon for the third time this summer, reaching nine major titles, there seemed to be a critical mass of articles saying Novak should be more appreciated. Have you seen any shifts in terms of the coverage he’s gotten over the years?

Bodo: Yes, he’s won people over. You know, I’m tempted to say it shows how fickle the media is, but that would take credit away from what he’s done, which is significant. And I don’t think it’s been calculated—I don’t think he’s this skeevy guy who decided that it’s going to serve his best interests to be nice all of a sudden. I think he’s just a guy who’s gone through a very appealing and heart-warming evolution into who he is today, which is a wonderful citizen of the world and tennis ambassador. He’s matured beautifully.

Still, I love the fact that he’s retained a lot of his original passion and he still cares about his country—he’s not one of these guys who doesn’t want to have anything to do with his roots. Some players in the past have wanted to escape all that—and they had good reason to in the past, given what they left behind.

It’s really a testament to what he’s done. He earned a renewed respect—he transformed the opinion people had of him through hard work and attitude and actions and success.

AM: How much do you think the coverage of Novak depends on the nationality of the writer or, more to the point, who he’s playing—say, the Brits and Murray? Even if you don’t read around, you must notice the kinds of questions Novak gets from them in press?

Bodo: I don’t read a lot; I do notice their questions. They’re fixated on Murray, just as the French are fixated on the Frenchmen. I think most of them are pretty fair, but they know where their business is. You don’t get as many of the antagonisms that you once did—there used to be that against German players. I remember (British writer) Rex Bellamy’s line about Becker, “It’s curious the Germans would take such a deep interest in a Centre Court that not so many decades ago they had chosen to bomb”—stuff like that. I guess he was trying to be clever, but it was definitely a dig. You don’t see too much of that any more. I think they’re generally pretty fair, but they’re looking out for their own guys and whatever rooting interest they have tends to be for their own people.

AM: They seem to play up the rivalry which, until Murray beat Djoković in Montreal, was pretty lopsided of late.

Bodo: None of that is, I don’t think, negative toward Djoković—they’re all just trying to whip up some kind of storyline and interest. We talked about this the other day: he knows that type of game is played.

AM: He even used the word “storyline” in responding to you, which I thought was interesting. Djoković has been asked, Becker’s been asked these kinds of questions: “Do you feel you get enough respect or appreciation?”

Bodo: See, that’s a storyline in and of itself now. That’s the next one. Sometimes it really helps to try to quantify these things. You know what? He’s appreciated in direct proportion to how much he’s won. He’s number three on the list—you can’t get around that—and he gets number-three appreciation. That’s pretty self-evident, I think.

People are awed by Federer—they’re “ga-ga” over him. He’s unique that way. Even Nadal doesn’t get that. Now that he’s down, you see that he never had the same aura. It’s not like they’ve abandoned him, but it’s awfully quiet out there in Nadal-land.

AM: It sounds to me that your perspective on Novak has been pretty consistent—is that the way you see it? Has there been a major turning point in your thinking about him?

Bodo: No, I don’t think there has. I’m kind of proud of the fact that I’ve always been accused by one camp or the other of being the other guy’s guy. You pick me up on Monday, and I’ve got a man-crush on Federer because I wrote that his hair was “lustrous” in a final. Then, you pick me up on Wednesday, and I’m ga-ga for Nadal; then, on Friday, I’m suddenly on the Djoković band-wagon and isn’t that unfair! I don’t like to shift intentionally, I try to catch myself and not to get too sucked into any of the narratives, and I like to look through different eyes sometimes. Frankly, if I look at my own work over time… I’ve taken my shots at all of them.

AM: Is there anything you find particularly interesting or challenging in writing about Novak?

Bodo: Frustrating? No, nothing actually. I love the stories about him when he was a little kid. I like this idea, this picture of him diligently packing his bag and waiting with his lunch—how earnest and sincere he must have been. I really, really like that.

You know, this isn’t just a Novak thing, but I regret in a way that the game has gone so far… When I started out, you really got to know these guys. They only occasionally became bosom buddies, but you could get fairly close to them if you covered them a lot. Not any more. So, I don’t really know these guys in the same way. I had one-on-one interviews with almost all of them when they were young, but not lengthy ones since then. And if I went now and made an effort, I could get an interview with this new kid coming up, Borna Ćorić. At the front end of my career, I would have known them much better as people.

Recommended Reading:

“The Perfect Player” (2007)

“Novak Djokovic, Roger Federer at heart of ‘great’ debate” (2015 US Open)