Novak Djoković is the most prominent Serbian citizen who has voiced his support for students who have been leading demonstrations since last November. How many people—at home or abroad—have heard his words?

The Background

Since the November 1, 2024 collapse of a concrete canopy outside the train station in Novi Sad, Serbia’s second city, students have been organizing regular meetings to commemorate the 15 lives lost as well as to call out the corruption they believe is behind the tragic accident. They have made a number of demands of the government, including the release of all documents relevant to the renovation of the train station and a 20% increase in funding for higher education. Universities have not held classes for months and students have organized sit-ins at faculty buildings as well as street protests.

Though the trigger for the protests—which have spread from Novi Sad and Belgrade to smaller cities and towns across the country—was quite specific, they quickly encompassed broadly-held sentiments: “For the students taking to the streets in their tens of thousands, the Novi Sad tragedy is emblematic of everything they believe is wrong in Serbia: widespread institutional corruption, a lack of accountability, and a technocratic class who are perceived to have risen only due to their ties to Vucic’s ruling Serbian Progressive Party” (Srpska napredna stranka, a.k.a. SNS, in Serbian). The government of President Aleksandar Vučić and his party, who have controlled Serbia for nearly 13 years, is in crisis as the student protests have galvanized citizens from all walks of life. On Friday, there was a general strike that slowed commerce and traffic in the capital to a standstill. And at a 24-hour blockade of one of Belgrade’s key intersections on Monday, students had backup from farmers on tractors, bikers, and white-coated medical staff. Professors, teachers, judges, actors, writers, and other professional and cultural groups have also signaled their support.

Vučić has suggested that the students are being funded by unidentified external actors who want to take down his government by force, and his rhetoric—by turns defensive, dismissive, defiant, and pleading—has likely contributed to acts of violence against the protestors. About two weeks ago, a student was injured when a car plowed through a crowded Belgrade street, an ugly incident that was caught on video; and on Monday, a handful of students in Novi Sad were beaten with baseball bats wielded by men who allegedly emerged from a SNS headquarters. Yesterday, only partly in response to the latter event, Prime Minister Miloš Vučević resigned, as did the mayor of Novi Sad, satisfying one of the students’ demands. With the prime minister’s resignation, the entire cabinet essentially collapses. What happens next is uncertain, although, “according to the Serbian Constitution, if parliament fails to elect a new government within 30 days of the prime minister’s resignation, the president is obliged to dissolve the National Assembly and schedule elections.” While opposition groups have called for the formation of a transitional government “made up of experts approved by the students,” the protestors themselves say they are not interested in “political power but accountability and justice within a corrupt system.” Those who can’t be on the streets and Serbs who reside abroad are refreshing their news feeds, exchanging frequent updates on messaging apps, posting photos of the protests on social media, and generally staying on alert.

Djoković Draws a Line

With a few notable exceptions over the course of his two-decade career, Djoković has generally been reluctant to make statements that his compatriots could perceive as political. (Why this is so is a complicated matter I’ll leave for another time. Anyone who can read Serbian or is willing to make do with an AI translation can consider the points raised here.) But over the last few years, beginning with environmental demonstrations in late 2021, his attitude has gradually changed. In the past month or so, after the student protests began, Djoković has seemed noticeably more willing to use his platform to address topics other than sports. As he told an interviewer last summer, for a cover story in the February issue of GQ magazine, “Tennis is still my biggest megaphone to the world.” This was among the reasons he listed for not yet hanging up his racquets, despite having completed his tennis bucket list with the gold medal in Paris.

On the other side of the world at the Australian Open, Djoković turned his megaphone toward home. After his third-round win over Tomáš Macháč, Novak wrote “for Sonja” and drew a heart on the camera, a dedication that would have come across loud and clear to anyone back home watching tennis and tracking the protests. Speaking with Serbian media, Novak explained the gesture. (The translations throughout are my own.)

It was addressed to Sonja [Ponjavić], who is currently in the hospital. I’m sending her support, and I hope that she recovers as quickly as possible. I was shocked, like everyone else, when I saw the video. I simply can’t believe that these kinds of things happen nowadays. I don’t know what clicks in a man’s head so that he’d do such a thing—to run over another person, not least a young woman, a student. Really. I don’t know what else to add, except, as always, to call for peace and understanding. I’m completely opposed to violence of every kind, and, unfortunately, it seems like there’s more and more of it on the streets. I hope it’ll stop soon.

Though these were his first words on the subject in a press conference, they weren’t Djoković’s first comment on current events in Serbia. In mid-December, he posted that he thinks it’s “important for [young people’s] voice to be heard.” Judging by the response on social media, some Serbs didn’t think he went far enough here, as this diplomatic statement neither mentioned the mass gatherings explicitly nor criticized the government. Given his reference to “educated youth,” however, the “with you” salutation is pretty clearly directed at protesting students.

However, his message from Melbourne’s Rod Laver Arena—one of the sport’s biggest stages—was an indication that Serbia’s favorite son had decided to make his statements on the subject more direct. (It’s worth noting that international media did not ask about this act, in stark contrast to the controversy that erupted when he wrote on a camera at Roland Garros in 2023. Since both messages were in Cyrillic, they required some deciphering; but activists on social media were happy to help when the subject was Kosovo and, thus, outrage was easy to generate.) After his fourth-round match, Djoković was asked a follow-up question—once again, in Serbian—related to his message on the camera. Specifically: does he follow the news from back home, or what’s happening around the world, when he’s competing at a tournament?

This time, his reply was much longer, even though he’d been asked a “yes or no” question and everyone in the room would have understood if he wanted to answer briefly and call it a day.

I follow what’s happening in Serbia—not quite everything, but I follow events a lot through social media. I can’t pretend that nothing is happening. . . Even though I’m in Australia, of course I’m upset by things like the situation that happened the other day with Sonja. I hope she recovers quickly and returns home. And that, unfortunately, isn’t the only instance of violence against students and young people. How can I put it? . . . This is a big loss for us as a society—Serbian [society], generally. So, my support is always with young people, and students, and all those to whom the future of our country belongs.

I mean, I can no longer consider myself a young man—I’m somewhere in middle age now—and I would like my children to also grow up in Serbia. I would like for young people from abroad to return to live in Serbia, and to feel that they have a society and an environment which they can enjoy and in which they can develop, and that it’s an environment that actually offers them everything that they need. So, that’s one thing I can say about that; and, of course, I always have been and always will be against violence of any kind. Really, I don’t know. I said this the other day and have nothing to add on that subject.

And in [the rest of] the world, what’s happening with wars, I have no comment on the fact that innocent people are constantly dying—they suffer the most. Honestly, sometimes I think: as an athlete, of course I want people from our country to support me, and I want them to feel, in some way, that what I do has value in their lives. . . . I am trying to be a good ambassador for Serbia in the world, and have been for many years. But, well, when these sorts of things happen, these kinds of tragedies—like Ribnikar or Novi Sad or everything that has happened in the last few years—then truly everything else, including sports and what I’m doing, falls into the shadows. It’s irrelevant compared to human life and to the struggle for some basic rights. That’s all I can tell you.

There is a lot in this statement one could unpack, like the tension Djoković appears to feel between his role as an informal ambassador and any criticism he might wish to make about the state of things in Serbia. But I’ll offer just three interpretations here. First, violence against young people—particularly the mass shooting at a Belgrade elementary school (OOS “Vladislav Ribnikar”) in May 2023—has almost certainly contributed to Novak’s new outspokenness. Second, both his age and his parenthood have shaped his thinking: he wants his kids, now 7 and 10 years old, to “also grow up in Serbia,” like he did, but it’s not certain that they will—not merely because they have the resources to live elsewhere but specifically because Serbia may not provide what they need to thrive. Third, while the exodus from Serbia over recent decades (essentially, since the breakup of Yugoslavia) saddens him, he understands it.

For more on “brain drain” from the Western Balkans, see below.

Research indicates that “young people leave these countries not only because of low salaries and economic issues but also because of corruption, crime, political instability and lack of security.”

To put this last point in context, I turn to Radio Free Europe: “For young Serbs, staying in their homeland is not easy, despite their love for their country. Youth unemployment is high, and many young people feel there is no other option than to find work abroad. According to a 2019 UNDP report, ‘Serbia is among the world’s 10 fastest-shrinking populations due to its low birth rates, high out-migration, and low immigration.'” These comments suggest that Djoković has a lot on his mind, including how he can best contribute to a brighter future for not only the children in his family but also the nation’s youth, more broadly. The work of his foundation, which focuses on early childhood education and has also been offering parenting workshops of late, is already making a difference. But is there more he could be doing? (I hasten to add that this is less my question than one I gather Novak is asking himself.)

Meanwhile, Back in Belgrade

What happened next may surprise and even shock some of you, though, unfortunately, it’s standard operating procedure in Vučić’s Serbia. That is: most regime-affiliated media didn’t report on Novak’s comments—not even those outlets which had sent journalists to Melbourne to cover his Australian Open campaign. They didn’t show his message to Sonja and they didn’t publish his lengthy follow-up observations, which were among the most revealing he’s ever made about contemporary Serbian society. Unlike the mostly-anonymous protestors—whom Vučić, other members of his party, and the media they control feel free to demonize—Novak Djoković is both a well-known figure and a wildly popular one. He also has a direct line for communicating with millions of people, irrespective of whether he’s giving an official press conference. Like the 20-somethings leading the protests, Djoković is accustomed to self-publishing when he feels the need: “The students haven’t just grown up with Vucic; they’ve also grown up with the Internet. Their flair for digital innovation and social media has enabled them to bypass state-controlled media and spread their message far and wide.” So, it isn’t easy to keep what he’s saying from his fellow citizens.

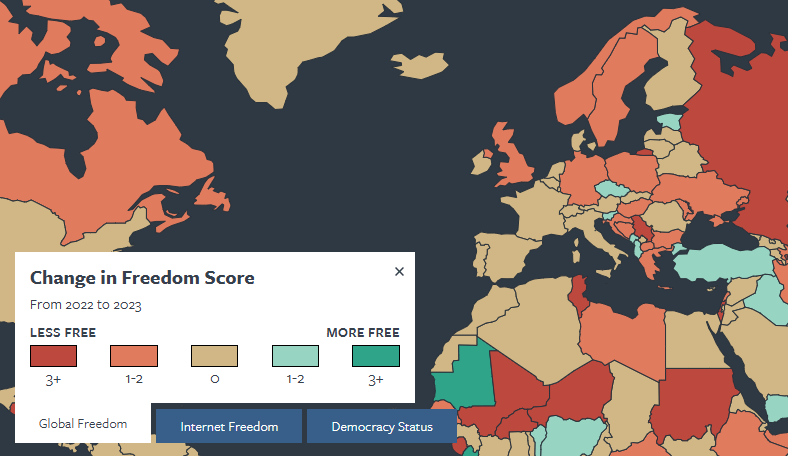

Nevertheless, members of the SNS are trying—through outright media control as well as the sort of “radical self-censorship” that has become common under Vučić’s increasingly authoritarian rule—to limit the reach of Novak’s voice. (Click these links if you want to learn about Vučić’s formative experience as the Minister of Information in the final, desperate years of Slobodan Milošević’s regime or about challenges to press freedom in Serbia.) A colleague, whom I won’t identify out of an abundance of caution, confirmed to me that he didn’t submit Novak’s protest comments because, simply, “Nothing of the sort gets published” by his SNS-controlled employer. Journalists working for such outlets are aware which subjects are forbidden and don’t even try to post these stories, as they know higher-ups will delete the material and they’ll likely lose their job.

Because Djoković made these comments in Serbian, they also didn’t get picked up by international media at the Australian Open. For this to happen, one of the Serbian reporters on site would have had to translate (and somehow circulate) Novak’s statement while also working on deadline to produce multiple articles a day. In any case, his comments weren’t sports-related; so, it’s doubtful any of the tennis beat reporters would have been able to do much with them. Thus, between the suppression of these comments at home and the lack of coverage abroad, it’s unlikely word of them has spread very far.

Acknowledgment

I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention that today’s New York Times features an article that mentions Djokoviċ in this context, the first I’ve seen in international coverage of the protests.

Serbia is a small country, with a population smaller than New York City’s, and most people in the world are unfamiliar with it. Unless there’s a natural disaster, heightened tension with Kosovo, or the Serbian men’s basketball team is threatening to upset the Americans at the Olympics, it’s not often in the international news—not since the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s, that is.

Sidebar

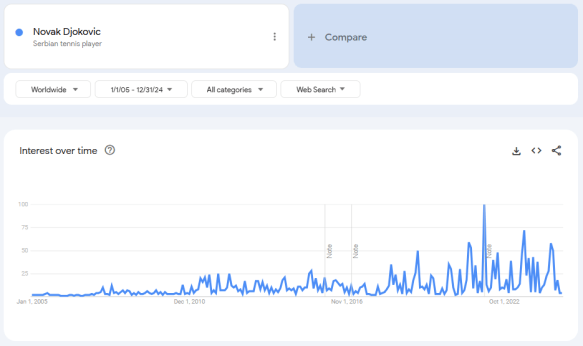

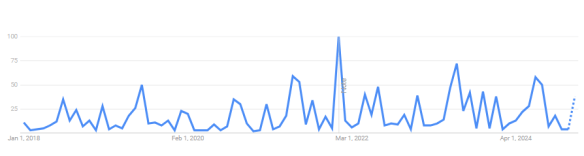

Out of curiosity, I looked on Google Trends to see whether Djoković got more global attention when he won the gold medal in Paris last summer or when he was detained and deported by the Australian government. The results were as I expected: there was far more interest in the January 2022 controversy than in any of his major titles. The five next-highest peaks (visible in the second slide) were during Wimbledon 2023, Roland Garros 2021, the 2024 Olympic Games, Wimbledon 2021, and Wimbledon 2019.

Still, what’s going on in Serbia right now is a big deal for the region. Something like this hasn’t happened for nearly a quarter-century. And the fact that the most recognizable Serb in the world went out on a limb to say something about it—and the Serbian government doesn’t want its own citizens to know—is arguably of much more significance than his having to pull out of a semifinal match at the Australian Open due to injury. Hopefully, Novak’s torn adductor muscle will be healed by the time the clay season rolls around, if not before. When—and how—the current crisis in Serbia will end is much less certain.

Postscript

On Friday, 31 January, Djoković made his first public appearance in Belgrade since returning from Australia a few days prior. At a basketball game between Belgrade rivals Crvena Zvezda and Partizan, he and his wife both sported custom-made sweatshirts expressing their support for students. (The phrase is a riff on the “dreamers are champions” theme from the collaboration between French designer Millinsky and Novak’s foundation.) In the video below, a reporter asks Novak to explain the meaning for those who don’t speak English, to which he replies, “They know—they know very well.” The media coverage of the game combined with a short statement in English more or less guarantees that this message, unlike the ones I discuss above, will be understood around the globe.