When was the last time you needed to look back decades—or even a century—to understand something that happened at a tennis tournament or other sporting event? If the answer is “never,” you’re surely not alone. But if you’ve ever tried to follow a regional controversy or grasp the relationship between sports and nationalism in the Balkans, it’s likely you’ve come across references to conflicts from long ago and the shadow they not infrequently cast over the present-day occupants of the region as well as the ex-Yugoslav diaspora.

I put together this post so that readers of my other essays will have at least some knowledge of the complicated history of the region known, in the 20th century, as Yugoslavia (literally, “land of the south Slavs”). Suffice it to say, this is no substitute for reading work by specialists, some of whose books I recommend below. It is, however, a start.

1) Slavic tribes migrated to southeastern Europe starting in the 6th century CE. From late antiquity, through the medieval and early modern periods, and right up to the end of the 19th century, this region was both part of vast empires (e.g., the Roman Empire) and made up of smaller provinces, principalities, republics, and kingdoms. Beyond the arrival of the Slavs, there are two key historic developments I think are worth highlighting here. First, the Great Schism: the split between the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches in 1054 (though even before this, the region was divided between the “Greek East” and “Latin West” spheres of influence). Second, the rise of the Ottoman Empire: specifically, incursions into and conquest of much of southeastern Europe, beginning in the mid-14th century.

For several centuries, the territory of what would become Yugoslavia after World War I was contested between the Habsburg (later, Austrian and Austro-Hungarian) and Ottoman empires, with portions of what are now Croatia, Bosnia, and Serbia part of a “military frontier” providing a buffer between the Ottomans and central Europe. It was also the site of regional resistance to imperial rule by the local Slavic populations. While Montenegro and Serbia gained independence in 1878 (following the tenth Russo-Turkish War and the Congress of Berlin), various Balkan conflicts continued until the eve of the Great War. Given all of the above, the population of this region is quite diverse: in addition to the south Slavic majority (which extends to Bulgaria), there are minorities of Albanian, Austrian, German, Greek, Hungarian, Italian, Roma, Romanian, and Turkish descent. Needless to say, there are people from the former Yugoslavia whose ancestry includes a mix of the aforementioned ethnic groups; likewise, there were many Yugoslav marriages between members of the Catholic, Orthodox, Muslim, &/or Jewish faiths.

2) What we now refer to as “the former Yugoslavia” was, in fact, two separate historical entities: from 1918-1941, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia (previously, the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes), a parliamentary constitutional monarchy; and from 1945-1992, the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY), led by Josip Broz “Tito” from the end of WWII until his death in 1980. The latter federation had the same basic external border as the former kingdom and included six constituent republics of Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia, Montenegro, Serbia, and Macedonia, plus two autonomous provinces, Vojvodina and Kosovo, within Serbia.

3) During WWII, something akin to a civil war took place within what had been the Kingdom of Yugoslavia; so, the fight wasn’t simply between Axis and Allied forces or German occupying armies and Yugoslav resistance fighters. Instead, there were multiple groups who were clashing for ideological &/or sectarian reasons. When the Royal Yugoslav Army surrendered to the Germans shortly after the Axis invasion in April 1941, the king and military leadership went into exile and many men of fighting age took up arms with other groups: namely, the Četniks (Serbian nationalist and royalist militias), Partisans (the multi-ethnic military arm of the communist party, to whom the Allies turned once the former group of rebels proved unreliable), and Ustaše (the Croatian fascist movement). While the Ustaše led a German and Italian puppet regime (the so-called Independent State of Croatia) and enacted a south-Slavic version of the “final solution,” the Četniks were a motley force of Serbian guerrillas who resisted or collaborated with the Axis powers more opportunistically, depending on both local circumstances and long-term goals. Yugoslavs may have joined forces depending on ethnicity, region, ideology, principle, pragmatism, &/or pressure, with some changing sides at different points in the war, including when given amnesty by the Partisans in the late stages of the conflict.

After the Allied victory and the subsequent formation of the Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia in 1945, both Ustaša and Četnik members faced reprisals under Tito’s leadership. The communist party’s principle of Yugoslav “brotherhood and unity” was reflected in the federal constitution and meant to promote both the peaceful coexistence of different ethnic groups and interdependence among the constituent republics. (The main highway across Yugoslavia, the first section of which was opened in 1950, was even named for this policy.)

4) Post-war Yugoslavia, despite being a socialist country, did not belong to the Eastern Bloc. Following the Tito-Stalin split in 1948, Yugoslavia made its own way (albeit with economic and military support from the US, especially in the early years of the Cold War). Declining to join NATO in 1953 or sign the Warsaw Pact in 1955, Tito played a leading role in the Non-Aligned Movement. Generally, Yugoslavia was a more open (i.e., liberal) society than the countries behind the “Iron Curtain.”

5) Following Tito’s death and ensuing political and economic crises, Yugoslavia broke apart in the early 1990s. Between June 1991 and March 1992, four of the six constituent republics—Slovenia, Croatia, Macedonia, and Bosnia—declared independence from the SFRY, leaving Serbia and Montenegro as “rump” Yugoslavia. (The latter entity, called the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia from 1992-2003 and the State Union of Serbia and Montenegro from 2003-06, lasted another 14 years.)

The dissolution of Yugoslavia and establishment of successor states was a protracted and painful process which included several distinct wars: a 10-day conflict between the Yugoslav People’s Army (JNA) and the Territorial Defense of Slovenia in 1991; the far longer and bloodier hostilities in Croatia and Bosnia, which lasted until late 1995; and the Kosovo war, which started as a years-long attempt by Serbian police to put down an insurgency by the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) and culminated in the NATO bombing of Yugoslavia in 1999. Although Kosovo declared independence from Serbia in 2008, the status of the territory remains unresolved. The United Nations maintains an “interim administration” in Kosovo, cooperating with local leadership as well as a number of other international organizations (including the EU and NATO).

In 1993, the UN established the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia in The Hague (Netherlands) to investigate and prosecute genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. All told, the ICTY indicted 161 individuals for crimes committed in the region between 1991-2001. When the ICTY was dissolved in 2017, other national and international judicial bodies continued its work. For example, as I write this, a trial of several former KLA leaders is under way.

Tennis fans should care about some or all of the above only if their interest in the sport extends beyond the rectangle that is the court. Some people watch tennis to escape from the real world—and that’s alright! But if you’re one of those fans who gets invested in a player and wants to better understand his/her background, the history of Yugoslavia may help. And, I hasten to add, this history isn’t merely relevant to Novak Djoković. Before anyone in the international tennis world even knew his name, there were four grand slam singles champions from the former Yugoslavia: Mima Jaušovec, Monika Seleš, Iva Majoli, and Goran Ivanišević. The last two decades have yielded a remarkable crop of players from the region, all of whom were affected, in one way or another, by the breakup of Yugoslavia.

Beyond that, there’s the old adage “knowledge is power.” The more you know about this history, the less likely you are to be confused, misled, or even manipulated by poor reporting or propaganda. Sports journalists often oversimplify these background stories or off-court incidents because, well, they’re on deadline and it’s not their job to cover history or politics. But there are also those—on social media, especially—who are operating in bad faith or from a place of ignorance &/or ideological investment. Their versions of events can thus be inaccurate, incomplete, or slanted for any number of reasons (including clout-chasing and trolling). So, I’d encourage anyone who encounters a controversial claim about a current player tied to the dark chapters of the Yugoslav past to verify the facts, research or seek out experts who can help provide the relevant context, and hold off on judgment.

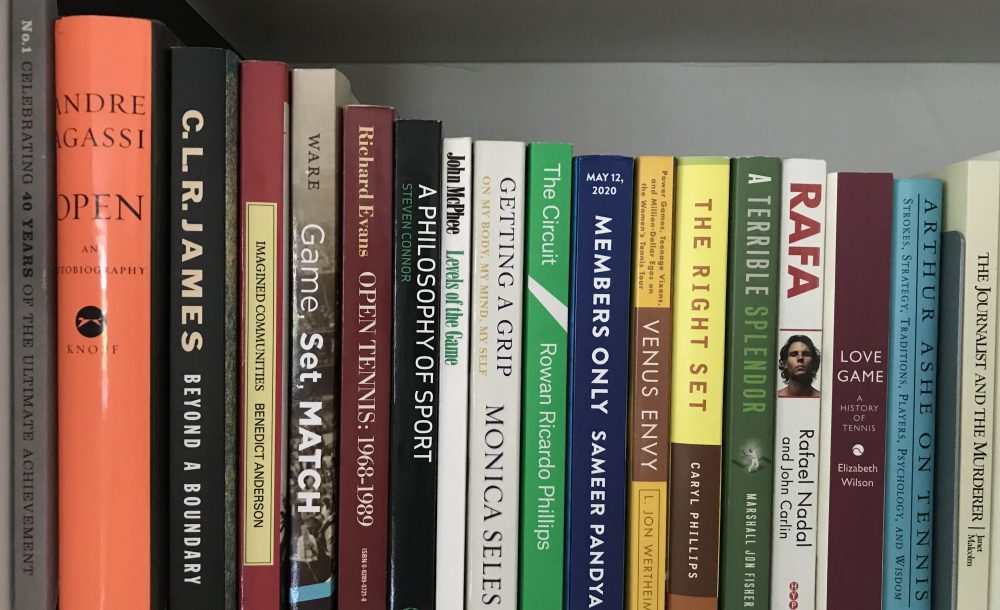

Selected Reading List:

This list includes both scholarly and journalistic work. Generally, I prefer to rely on academic experts; but I acknowledge that their published work, often addressed to other specialists, can be dense and dry. Nevertheless, I’d urge caution with regard to journalistic coverage of both the history and politics of the region, especially the books produced in the midst of the 1990s conflicts. A similar warning applies to the Wikipedia entries for any of the aforementioned topics: although they are often good starting points, they can also contain revisionist history influenced by the ethnic nationalism that is sadly widespread in the Yugoslav successor states.

Catherine Baker, The Yugoslav Wars of the 1990s (2015)

John V.A. Fine, Jr., The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century (1983) and The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest (1987)

Patrick J. Geary, The Myth of Nations: The Medieval Origins of Europe (2003)

Misha Glenny, The Balkans, 1804-2012: Nationalism, War and the Great Powers (2012)

Tim Judah, The Serbs: History, Myth and the Destruction of Yugoslavia (3rd edition 2009)

John R. Lampe, Yugoslavia as History: Twice There was a Country (2nd edition 2000)

Sabrina P. Ramet, Thinking about Yugoslavia: Scholarly Debates about the Yugoslav Breakup and the Wars in Bosnia and Kosovo (2005)

Laura Silber and Alan Little, Yugoslavia: Death of a Nation (1997); accompanying BBC documentary series