Despite the title, this isn’t really a post about Srdjan Djoković. Like various others during the second week of the Australian Open, I’m using the father of the top men’s player in the world to get your attention. Unlike many of them, I’m doing so for what I hope is an edifying purpose. Namely, I want to unpack a widely-reported incident that took place outside Rod Laver Arena last month in order to make distinctions between different types of information. In the second part of the post, I’ll offer an interpretation of the varieties of fan sentiment, ethnic pride, nationalist iconography, &/or political ideology that were expressed on the tournament grounds after the quarterfinal match between Novak Djoković and Andrey Rublev.

Part 1

First, the facts: Following complaints by spectators during a first-round match between Kateryna Baindl (UKR) and Kamilla Rakhimova (RUS), as well as a demand from the Ukrainian ambassador to Australia, Tennis Australia belatedly introduced a ban on Russian and Belarusian flags. Over the course of the subsequent 12 days, they added more flags, banners, and symbols to the prohibited list in order to cast a wider net for potentially-provocative displays by attendees.

Though there may have been others who managed to sneak in flags here and there (and we know that security ejected unruly spectators for a variety of reasons throughout the fortnight), it wasn’t until the middle of the second week that there was a news-making incident involving about six men waving Russian (and related) flags and chanting pro-Putin slogans on the steps leading from the two main show-courts into Garden Square.

The timeline: Djoković’s on-court interview ended around 10:00pm; shortly thereafter, Novak fans began to assemble on the steps, as they had after each of his wins. Though at least one of the aforementioned men is visible in the background of my videos and photos of the festivities, it wasn’t until the significantly larger group began to disperse, at approximately 10:30, that these men briefly took center stage.

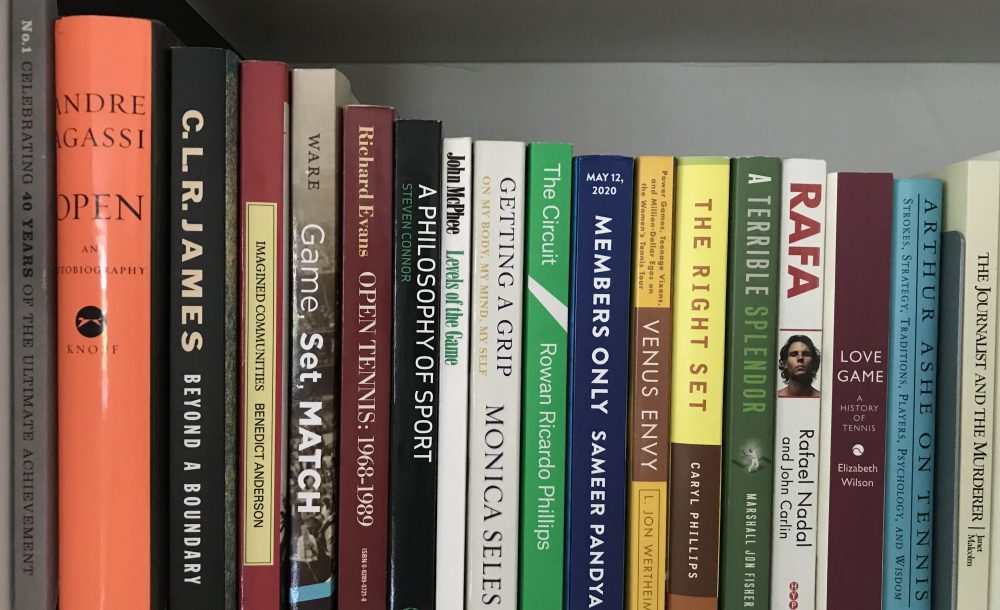

A few minutes prior to that, some of the men in question had stopped Srdjan Djoković for a picture as he was leaving the fan gathering. As can be seen in the photo below, the main culprit is not only holding a flag emblazoned with Vladimir Putin’s face but also wearing a t-shirt with a “Z” symbol over the Night Wolves logo. (I’ll discuss the significance of these accoutrements in Part 2.)

Within minutes, event security confronted the men and escorted them from the site, where they were questioned by Victoria Police.

For the record: while I spent some time observing the celebration, and walked past Srdjan and his entourage on my way from the media center to the steps, I left the area 5-10 minutes before things got ugly. So, unfortunately, I’m not in a position to say whether people were dispersing organically or began leaving due to these men’s disruptive behavior. (I do know, however, that some fans wishing to say hello to Novak’s father turned away when they saw these men approaching him.)

In the background: An ethnic Russian activist named Semyon Boikov, who also goes by the name “Aussie Cossack,” had encouraged his social-media followers to “retaliate” against Tennis Australia for what he called their “discrimination,” “racism,” and “attack on honor and dignity” in banning various Russian flags. The very day TA announced the ban, Boikov offered a cash reward to anyone who succeeded in displaying a pro-Russian symbol during a televised match and provided a helpful list of all matches featuring Russian players. Subsequently, he congratulated attendees who had managed to evade the ban, before specifically suggesting the Djoković-Rublev quarterfinal as a high-profile opportunity to do so. In all, Boikov—who has some 161,000 YouTube subscribers, solicits volunteers, and raises money off his content—published twenty-two posts and videos about Russian flags at the Australian Open on his channel over a two-week period.

Assessment: Clearly, the Tennis Australia flag policy and the security measures in place to implement it weren’t enough to stop people determined to bring banned items into Melbourne Park. In fairness, though, it’s pretty tough to thoroughly search the bags—and bodies—of each of the tens of thousands of people coming through the gates every day; and AO security had the additional challenge of distinguishing between similar-looking Russian (🇷🇺) and Serbian (🇷🇸) flags. In a few cases, members of the security team were over-zealous with flag-draped fans there to support Djoković; in a handful of other cases, they missed people who, I think it’s safe to say, had ulterior motives for coming to the tournament on the day(s) they did. All things considered, my main criticism of the AO is that their security staff didn’t act sooner to remove these men. But, even so, my criticism is qualified, as there may have been other factors contributing to their decision, such as waiting for police back-up or prioritizing the safety of the larger crowd by delaying action in order to minimize chances of people getting hurt should any violence erupt as they attempted to detain the men.

Afterwards: In the interest of transparency, I’ll confess that I jumped to conclusions when I first saw the headlines about Srdjan Djoković. Anyone who has followed Novak’s career knows that the father has often been a public-relations liability to the son; and I’ve followed it more closely than most—not least, because I speak Serbian. So, I reacted to the photo a colleague sent our Serbian media group chat late Wednesday night by rolling my eyes. The next day, I reacted to the flurry of tweets I saw when I first checked Twitter like a lot of other people did: by making a judgment without clicking the accompanying links and reading the articles, never mind watching the video “evidence” and evaluating its source. And I did this despite having more contextual information at my disposal than most people, not less. So, this whole episode was a salutary reminder for me, too: slow down; take a breath; read the article; check the source; try to keep your confirmation bias at bay; and consider what else you know or where you can look for more information. Also: since no one needs to tweet (ever), there’s no professional obligation or journalistic value in tweeting about an event before you have the facts straight.

In terms of the way this incident was covered in the first 24-36 hours, I’d suggest readers look at when stories were published or broadcast, which outlets published or broadcast them first (and which waited on details), whether they were published online only or also in print (the editorial standards for the latter are generally higher), what sorts of reporting they were based on, and how they were framed. Five things, in particular, stand out to me:

- Many stories were published too soon after the incident to allow for much reporting (e.g., verification, interviews, & research) or even fact-checking.

- The main character of the stories shifted very quickly from a group of disruptive men tossed from Melbourne Park to Novak’s father.

- None of the articles that I read or news segments that I watched quoted eyewitness accounts (by the journalists themselves or spectators who had observed the events in question).

- Many of the reports highlighted an inaccurate translation based on a questionable quotation of what Srdjan Djoković said to the men, often in the headline or subhed.

- The primary source for most stories, other than a Tennis Australia press release, was a video created by the culprits themselves, which included misleading edits, descriptions, and subtitles provided by the “Aussie Cossack” channel.

As a result, stories presented a mix of accurate information (Srdjan did indeed pose for a picture with two of these men), misinformation (the misquotation and inaccurate translation), and speculation (e.g., attempts to interpret the deeper meaning of Djoković senior’s behavior based on an incomplete &/or inadequate grasp of the facts). On top of that, the stories also—albeit inadvertently—spread disinformation by amplifying a propaganda video made to manipulate viewers and advocate specific ideological and policy positions.

To expand on the disinformation point: even if one didn’t witness the scene that night or have enough information at hand to be able to spot the inaccuracies in the video posted by “Aussie Cossack,” one can make some inferences by viewing it in context. Specifically, who filmed the two parts of the incident: 1) the “photo” of Srdjan with two supposed Novak fans that abruptly (and presumably without explanation to Djoković senior) morphed into a video greeting to Alexander Zaldostanov; and 2) the group unfurling Russian flags and cheering Putin on the steps? Though The Guardian’s Tumaini Carayol happened to catch these guys in the latter act, they certainly weren’t leaving it to chance. Why were their short clips then featured in a longer video (set to patriotic Serbian music!) produced for social-media consumption? What can be gleaned about these fellows from a) what they were wearing, holding, and saying; b) the YouTube channel to which they submitted their cell-phone videos; &/or c) a simple Google search for either Boikov himself or the Night Wolves motorcycle “club”?

An aside: the initial media cycle lasted less than a day before it moved on to stories about reactions to the incident—interestingly, more to Srdjan Djoković himself than to the flag-ban-evading, political-statement-making culprits. If you’re interested in journalism, I’d recommend reading a post by NYU professor Jay Rosen about “scoops.” Rosen opens by observing that “Journalists tend to be obsessed with scoops, meaning: the first to break the news, and being seen as the first, which means getting credit for it among peers. But not all scoops,” he continues, “are created equal.” I’ll leave it to others to determine what kind of “scoop” the Srdjan story was—and how well the initial reports held up.

Jay Rosen, “Four Types of Scoops”

Answering only part of the last question: Boikov is someone with a substantial record of both pro-Russian activism in Australia, where he was born, and propagandistic videos and appearances on Russian television. Additionally, Boikov has stated, “We never felt ourselves to be Australian, we were aliens there. I consider myself to be a Russian.” He is not, to put it mildly, a reliable source. In fact, he has made his “Aussie Cossack” group’s motives quite clear in interviews: “We’ll always support the policies of the [Russian] state, we respect very much our Commander-in-Chief, Putin. And we have a unique capacity to support Russia from within a hostile state. Even the FSB or a battalion of the Russian SAS can’t achieve that, because unlike them we are citizens of this state.” Enough said. Why journalists would take what Boikov says on any subject at face value is beyond me.

To make matters worse: while most of Boikov’s videos have below 50 thousand views, the much-embedded, linked, and shared video about the “bold political statement” Srdjan Djoković supposedly made now has 181 thousand views. By every measure imaginable, this was a propaganda win for “Aussie Cossack” and his allies—not because his content is the work of a sophisticated genius but because so few media outlets could resist the lure of a controversy that could be tied to Djoković.

More to follow…