After the ITF announced plans to overhaul the 118-year-old Davis Cup tournament with the help of a $3 billion infusion from Kosmos investment group, Tennis Channel chose the question “Has the ITF gone too far?” for its weekly “Tough Call” debate. To me, this

isn’t a close call: the ITF’s proposed changes would fundamentally alter the nature of the Davis Cup, with national-team competition virtually the only feature remaining. Home and away ties, the life-blood of the event, are gone. The competition is squeezed into a single week; ties (of which there would be 25, up from 15) are reduced from five rubbers to three, matches from best-of-five sets to three; and fans won’t be able to plan ahead to support their team’s efforts in the all-important final weekend (as they have ample time to do with the current format), since the contestants won’t be known until Thursday or Friday. A final in a neutral venue, which was part of last year’s failed bid, doesn’t sound so bad now that we’re facing the prospect of neutral fans—that is, those who bought tickets without having any idea which teams would make the final. The ITF itself isn’t referring to mere “improvements” (which is what their strategic plan, ITF2024, identifies as a priority) but to the “transformation” of Davis Cup, going so far as to say that they’re creating a new event—albeit one with a derivative name: the “season-ending World Cup of Tennis Finals.”

This leads me to two, over-arching questions. 1) Does professional tennis really need a “major new” annual tournament? (Never mind, for the time being, subordinate questions about the proposal’s specifics: e.g., is late November the best time in the tennis calendar to stage such a competition?) 2) What gap in men’s tennis does this proposal fill—or, more to the point, what problems about Davis Cup as-is does it aim to solve?

Here’s what I know to be true: players in the World Group (though what percentage, I’m not sure anyone can say) have complained about the Davis Cup schedule. Some focus on its proximity to the majors, noting that it’s difficult—particularly for those who regularly make deep runs—to turn around and hop on a plane to another time zone, often playing on a different surface from both the previous and the subsequent tournament. Some think four weeks a year is too big a commitment or suggest the event take place biennially, not to conflict with the Olympic games. Some would likely welcome a reduction from best-of-five sets to three, to make the ties less (potentially) grueling and decrease risk of injury. Many, no doubt, wish ATP points were still on offer and certainly wouldn’t look askance at more prize money.

What’s confusing to me: why the ITF took player complaints about the schedule and frequency of Davis Cup ties and decided to address them with this set of format changes. Were European players and fans—that is, those who’ve largely comprised finals participants for well over a decade—clamoring to fly to Singapore a month after the end of the ATP’s Asian swing?

We keep hearing the Davis Cup is “dying” and that such comprehensive changes are inevitable, even necessary. (“It’s either this or get rid of it,” says Mardy Fish.) Is it really in a terminal state? When and how was its condition diagnosed? The absence of top players from the field is the most frequently-cited reason, followed by the competition’s diminished “relevance.” Things sure sound dire. But rarely is concrete evidence of the competition’s demise on offer, even in texts of longer than 280 characters. For example, though the New York Times noted this week that the competition is “losing traction globally,” nowhere did the article provide a specific example of what this loss entails or how it registers in various parts of the tennis world. Yes, it’s said that this slow, painful death has resulted in fading prestige: winning the trophy doesn’t mean as much as it once did. But how are such things as meaning measured?

In some cases, contributing factors are pretty easy to quantify and confirm or dispute. For instance, the oft-repeated claim that the “top players” don’t participate is overstated. Again, Fish: “What stars? No one played anymore[,] dude”—an especially odd observation from an American given that the best U.S. players, like John Isner, consistently commit to the national team, and the Bryan brothers recently retired from Davis-Cup duty after 14 straight years of service and a 25-5 doubles record. (See here and here for more numbers that rather undermine such statements.) Not only have all of the most-decorated players of this generation won the Davis Cup—Spain, with and without Nadal, four times since 2004—but most other eligible top-50 ranked players also take part annually.

In 2017, 15 top-20 players competed; in 2016, it was 16 of the top 20 and 24 of the top 30. Prior to a few years ago, the ITF didn’t even publish such statistics in their yearly roundup—perhaps because they didn’t feel the pressure to combat this common, but misleading, line.

Being the skeptical sort, I’d like to see more proof of the Davis Cup’s ill health. So, I’ve got questions, ones that I challenge the tennis fans and journalists among my readers to answer. As you’ll no doubt note, all of the below pertain to the World Group—rather unfortunately, the only part of the Davis Cup that gets much attention (about which, more later).

A. Is the Davis Cup losing money annually? If so, since when and how much? When did it make more? What is the competition’s annual revenue and how is it distributed among national tennis federations? How much (more) does the ITF need to make—from the World Group contests, in particular—in order to fund its development programs at current and/or desirable levels?

B. Have Davis Cup ticket sales, especially for the final, been decreasing over the years? This seems unlikely, given that five of the six biggest single-day crowds have been recorded in the last 14 years, but I suppose anything is possible.

Was there a time when considerably more than half a million spectators (which seems to be the standard of late) attended Davis Cup ties over the course of a season? If so, when was the sales peak and is the decline since then steep or significant? Some point to the 2014 final, in which a Federer-led Switzerland beat a charismatic and deep French team in front of 27,448 fans at the stadium in Lille, as if it were some sort of anomaly. But the fact is that over 530,000 spectators attended the Davis Cup in 2017 and the final Sunday crowd—there to cheer on as Belgium’s David Goffin unexpectedly beat Jo-Wilfried Tsonga and Lucas Pouille secured the championship for France by defeating Steve “The Shark” Darcis—was some 26,000 strong. (With the exception of Tsonga, I’d respectfully suggest, none of those four players is a particularly big draw outside their home country.) The numbers in other recent years don’t look terribly different: in 2016, sell-out crowds (including an enthusiastic Diego Maradona) watched Croatia and Argentina go the distance in Zagreb’s 16,000-seat arena; and even in 2013, when a depleted Serbian team hosted the Czech Republic, 46,000 fans attended the season finale in Belgrade.

C. Has the number of people watching Davis Cup on tv (or via streaming services) dwindled over the decades? Have fewer networks been carrying the event live? Are the tv contracts worth less now than they were at some point in the past? Is the Davis Cup broadcast in fewer countries than it was 10, 20, or 40 years ago? How does coverage and viewership for the tournament final compare to that for an ATP Masters 1000 series event (not, mind you, a “combined” event like Indian Wells), the World Tour Finals, or the Olympic men’s singles final?

I’ll just leave this here, as they say.

D. Are regional or global sponsors hard to come by? Overall, are sponsorships lucrative, adequate, stable, or shrinking? Here’s a year-end note from 2015.

E. Has there been a decrease in website visits and fan social-media engagement over the past decade or two? From where I’m sitting, the 2017 numbers looks pretty good; admittedly, though, I’m no expert on such matters and have no real point of reference.

By what means, other than those I’ve identified above, do or did the ITF and tennis pundits gauge world-wide interest, particularly before the internet era?

F. Are fewer articles being written about Davis Cup—first, in host and guest nation publications; and second, in global sports outlets? Are significantly fewer foreign print media attending than they did in the past (and is this number out of step with developments at other tennis tournaments)? If an editor doesn’t send his/her tennis reporter to cover Davis Cup, how do we know that’s a reflection on reader interest rather than on the current state of journalism in general and tennis media in particular?

If we’re lucky, someone more technologically adept than I will explore Google trends or a similar site and report back. (Former Yugoslavia, represent!)

G. More generally, when we hear that this competition is less meaningful, prestigious, or valuable than it used to be, on what are such assessments based? Not everything can be quantified, I realize, but surely those who’ve reached this conclusion can better substantiate it—at least, if they hope to persuade others who don’t already agree.

When the Davis Cup of today is found lacking, to what is it being compared: its own (apparently glorious) past, grand slam tournaments (which are, it’s worth underscoring, dual-gender events), finals in other sports, and/or competitions that currently exist only on paper? Are these comparisons reasonable? How much of what we imagine the Davis Cup could or should be is filtered through nostalgia or a result of wishful thinking?

For instance, is it useful to model an annual national-team tennis tournament on the World Cup, which takes place every four years and involves a lengthy continental qualification process? Does it make sense to suggest Davis Cup should be more akin to a year-old exhibition like the Laver Cup or even a longstanding competition such as Ryder Cup, both of which take place in a long weekend and involve only two teams (and, thus, no preliminary rounds)?

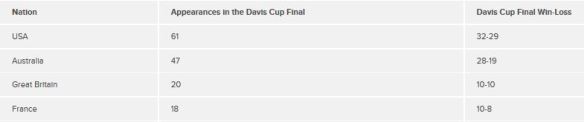

Is it even fair to compare the current iteration to the Davis Cup’s past, when the entire tennis—not to mention global sports—landscape looked dramatically different and its seasonal calendar was much less full? After all, during the first seventy years of the competition, fewer than fifty nations participated and the trophy was monopolized by the four slam nations. (Belgium, by the way, was the first other country to make the Davis Cup final: they got crushed by the Brits, 5-0, in 1904. Japan, in 1921, was the next—and they didn’t fare any better against the Americans; it would be almost 40 more years for another outsider, Italy, to be subject to a similar defeat at the hands of the Aussies.) Of course it’s not going to mean the same thing now, with 125 countries competing, as it did in an era when the professional tour was just getting started—and especially in the decades immediately before that, when the event was essentially an extended grudge match between the U.S. and Australia. But just because the place of the Davis Cup in men’s tennis has changed, so it means something different from what it did in the days of Roy Emerson and John Newcombe, Stan Smith and Arthur Ashe, that doesn’t necessarily make it less meaningful. Though the British public may not have been quite as thrilled by the 2015 Davis Cup win as they were when Andy Murray ended the 77-year British men’s singles title drought at Wimbledon two years prior, for example, not even playing on the clay in Ghent seems to have dampened Team GB’s enthusiasm for the occasion.

Of course it’s not going to mean the same thing now, with 125 countries competing, as it did in an era when the professional tour was just getting started—and especially in the decades immediately before that, when the event was essentially an extended grudge match between the U.S. and Australia. But just because the place of the Davis Cup in men’s tennis has changed, so it means something different from what it did in the days of Roy Emerson and John Newcombe, Stan Smith and Arthur Ashe, that doesn’t necessarily make it less meaningful. Though the British public may not have been quite as thrilled by the 2015 Davis Cup win as they were when Andy Murray ended the 77-year British men’s singles title drought at Wimbledon two years prior, for example, not even playing on the clay in Ghent seems to have dampened Team GB’s enthusiasm for the occasion.

♠♣♥♦

As is likely obvious by now, I love the Davis Cup. Still, despite its being one of my favorite sporting events of the year, I certainly agree it can be improved. I also believe it’s really important to identify—and understand the precise nature of—the problem before considering potential solutions. Because even though I think reports of its death have been greatly exaggerated, it’s clear Davis Cup does have a problem. Or the ITF does, anyway.