Preface: I posted parts of this introduction in December, then decided to hold off on the rest until the completion of Troicki’s ban. Now that he’s returned to action, the time seems right to reflect on what we did and didn’t learn from his case.

In a review of the 2013 tennis season, Steve Tignor called doping suspensions the “controversy of the year.” Here, I’ll focus on reactions to the case that generated the most debate, aiming to develop a point Tignor makes at the outset of his column: “the game’s testing system remains a learning process for all concerned.” Perhaps unlike him, I consider those concerned to include not only players and doping authorities but the tennis media and fans as well. Because I’m not writing for a tennis publication, I’ve also got more latitude in drawing four general lessons from Troicki’s case and connecting them to issues in the wider world. So, expect fewer citations of anti-doping policy from me and more references to psychology, philosophy, and even literature (does Peanuts count as “literature”?).

As will become increasingly clear, I’m interested in one dimension of the Troicki story above all others: the mental-health angle (an imperfect phrase I’ll parse in lesson 2). Why this is so has partly to do with the extent to which it seems to have been neglected in most discussions of the case, and partly to do with how important the matter of mental health is—not simply in this specific instance, or sports more generally, but in life.

After this introduction, I’m not going to rehearse familiar details of the case, as they are available for all to read and have been dissected elsewhere. Instead, I want to stake out a position from the start: I believe this incident, including how it was resolved, raises more questions than many others writing about it (not least, those publishing 140 characters at a time) seem to. Further, I don’t think it makes sense to separate the issue of whether Troicki submitted the required blood sample that spring day in Monte Carlo from that of why he did or didn’t do so—something we can’t address without exploring his needle phobia in greater depth. Troicki’s failure to fulfill his professional responsibilities has gotten plenty of attention. What has generated less discussion than I think they deserve are his rights—how he should, ideally, have been treated as both a professional tennis player and a human being.

✍✍✍

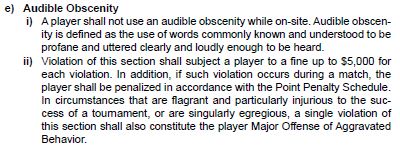

Analyses of the case, including the ITF’s Independent Anti-Doping Tribunal (IADT) and Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) appeal decisions, tend to rest on three questions. The first is about as straightforward as they come: “Did Viktor Troicki give a blood sample immediately after he was notified that he’d been selected for testing?” Since Troicki himself doesn’t dispute that the answer to this is “No,” most concluded that he had clearly broken an anti-doping rule and moved on to the second question, one of judgment rather than fact: “What is the appropriate sanction for this violation?” Not even Troicki’s staunchest public defender, Novak Djoković, argued that his compatriot bears no responsibility for what transpired in Monte Carlo: “as a tennis pro, our job is to play, of course, tennis and respect all the rules and know all the rules of our sport…. I’m not saying that it’s completely not his fault,” the Serb acknowledged during the World Tour Finals in November. But because he nevertheless regards the outcome of the appeal as a “total injustice,” we can assume Djoković disagrees with the CAS on the stickiest point: “Did Troicki have a compelling justification for failing to provide a blood sample?”

Like many others viewing the case, the then-ATP #2 zeroed in on the “he said, she said” conflict between the player and the Doping Control Officer (DCO) as central to the case. (Though one is tempted to refer to them as “patient” and “doctor,” this is would be a mistake, for reasons I’ll elaborate in lesson 1.) Did the DCO tell the player that “it will not be a problem” and it “should be all right” if he didn’t give a blood sample that day, as Troicki claims (16c, 3.13.1*)? Whereas the IADT found the DCO’s account much more credible than Troicki’s (and thus concluded the DCO had not offered “an unequivocal assurance” [39I]), Djoković, unsurprisingly, believed the word of his friend of nearly twenty years. Though they still assigned the player a degree of fault, the CAS panel scrutinized the DCO’s role in the interaction more closely, calling it “a misunderstanding,” enumerating a number of the DCO’s “acts and omissions” that contributed to it, and reducing Troicki’s suspension to the ITF-mandated minimum of one year (9.9, 9.14). As Tignor has observed, “Djokovic may not agree with the CAS’s decision, but the CAS agrees with him,” offering both criticisms of the procedure and suggestions for how it might be improved. Given that the CAS determined Troicki bore “no significant fault or negligence” with regard to the rule violation, it’s entirely possible they would have reduced his penalty still further had that been an option. (*Parenthetical citations refer to paragraph numbers in the two rulings, abbreviated I for IADT and C for CAS.)

I take a different position from both Djoković and the CAS, though I similarly focus on the interaction between player and DCO, as well as between the DCO and others, including her supervisor at IDTM, to whom she reported immediately after the initial encounter. (Those familiar with the case will recall that player & officer met again the next day, at the latter’s initiative; see 21-24I and 3.22-25C for details). Troicki’s team argued that the case against him should be dismissed due to four intertwined factors: not that “the facts of his illness at the time, his phobia of needles and his panic at the likely physical consequences for him of giving blood would of themselves amount to ‘compelling justification’” for not providing a sample that day but, rather, that these three things “in conjunction with” the DCO’s assurances do (38I). Based on my research, I believe their interaction was likely complicated by additional factors not discussed in the IADT report and mainly alluded to by the CAS: namely, that Troicki was not aware of his rights—particularly, but not only, as a player with a disability—and that the DCO was both unaware of (or ignored) other options available to her and ill-equipped by her training to handle someone experiencing a phobic reaction to the prospect of a needle procedure. Ultimately, both of the latter, if accurate, are failings that must be addressed at the administrative level by the ITF.

Because I was not in the room last April and, more importantly, am not an expert on needle phobia, some of my claims are necessarily speculative. (Call those “thought experiments,” if you wish.) The evidence I invoke to support my points, I hasten to add, is not. My view, developed at what is almost certainly too great a length for most readers, is that Troicki’s was a mismanaged disability case, in addition to—or perhaps more so than—a case of a Tennis Anti-Doping Programme (TADP) violation. In other words, I believe the above-mentioned circumstances amounted to compelling justification for Troicki’s breaking the rule in question. In the best-case scenario, of course, that would have been avoided altogether through a joint effort by both player and DCO, in consultation with other officials on site and in line with established policy. However, I don’t believe that Troicki’s condition at the time or lack of awareness of his rights is a justification for representatives of the ITF not to respect them, either during or after the fact. It’s obviously too late now for the CAS to reconsider the case or for Troicki to get a year of his professional life back. But given that similarly challenging situations may arise, with Viktor or another needle-phobic player, both the ITF and those governed by their rules need to be better prepared. In order for that to happen, policy and procedure related to the taking of blood samples require updating, and affected players and staff need educating. Such things, in short, will require advocacy and follow-through on someone’s part. While, to my knowledge, no one with power to effect change is actively discussing these issues or pursuing them through concrete steps, I hope to be corrected.

✍✍✍

From Umag, where Troicki first learned of the ITF’s decision to suspend him, to Washington, where other ATP players responded to the news, from Belgrade to Beijing and London to Lausanne, this case made for much controversy. On Twitter, in online comment sections, and in press conferences—not least, of Serbian Davis Cup team members—there was often more heat than light. The source of this heat ranges. Look and you will find strong emotions, misinformation, ignorance, hyperbole, conspiracy theories, and (what is to me) unwarranted certainty. Also significant are a number of oversights, oversimplifications, and silences, the reasons for which may be more difficult to pinpoint.

In case anyone reading needs this reminder: learning is a lifelong process. Here are highlights from the lessons I’m taking away. For further discussion &/or more sources, please click on the individual section numbers.

1. Do your homework.

A little learning is a dang’rous thing;/ Drink deep, or taste not the Pierian spring. There shallow draughts intoxicate the brain,/ And drinking largely sobers us again.

—Alexander Pope, An Essay on Criticism (1711)

Different tennis constituencies—including players, the ITF, and sports journalists—have work to do in order to avoid or better respond to similar situations in the future. Many discussions of the case have focused on Troicki’s seeming naiveté or ignorance of the TADP, suggesting the problem never would have arisen if only he’d known and followed “the rules”—that is, had he not sought a partial exemption from them in the first place. This section identifies and discusses a number of other things that the case and subsequent coverage reveal need, at minimum, review.

Troicki’s resistance to having his blood drawn at the requested time was greeted with surprise and incredulity in both media and player circles. A typical response, for instance, was to point out that “the rule is there for a reason and is pretty simple.” The thing is, there’s not much evidence to support the claim, made by too many to name, that Troicki disregarded or didn’t understand the rules. He reported to the Doping Control Station directly after his match, gave the required urine sample, and then asked to be excused from giving blood; he also delayed signing the requisite form until after he’d had a discussion with the DCO. Say what you will about those last two steps and their implications (and I’ll say lots more about the former), the fact is that neither of them is against the rules and actually show an awareness of them. Nevertheless, people discussing the case and Troicki’s reaction to the penalty implied that he “arbitrarily” broke the rules by “skipping” a test, as if he rather capriciously failed to show up altogether, and was then confused about why he got in trouble.

One of the most frequently misrepresented aspects of the case is the suggestion that Troicki asked to and “claims he was told by the ITF official that he could take the test the next day.” In fact, Troicki did not ask to take the blood test the next day. What he was after was not a 24-hour delay but a pass, essentially, until the next time he was randomly selected for testing. Per the IADT report, “he asked if there was any chance that he did not have to give blood on that occasion” (15b). In Troicki’s own words, from the explanatory note he appended to the required form: “I always did blood tests before, and I [will] do them in the future, but today I was not [able to] provide [a] blood sample” (15e; my emphasis). That he ended up giving blood the next day is almost entirely a result of the fact that the DCO herself initiated contact with him. She went looking for him, enlisted the ATP supervisor’s help in finding him (recall that, as he had lost the day before, Troicki was officially out of the tournament), and told Viktor “there could be a problem” (see sections 21-24I). Upon hearing that, as if for the first time, the player then asked, “Does it make any sense to do the blood test today, since I am feeling better today?” If the DCO were entirely confident about how she’d handled the previous day’s encounter, would she have gone in search of him and would he have had the opportunity to ask this question? We’ll never know. But the fact is that she certainly didn’t need to talk to him or take his blood the next day. Nor was that procedure something Troicki, who left the DCS the day before thinking he’d gotten out of the blood test altogether, is likely to have requested if left to his own devices. Why this is so will be discussed in the next section.

2. Feel free to admit when there’s something you don’t know.

Socrates: “Well, I am certainly wiser than this man. It is only too likely that neither of us has any knowledge to boast of; but he thinks that he knows something which he does not know, whereas I am quite conscious of my ignorance. At any rate, it seems that I am wiser than he is to this small extent, that I do not think that I know what I do not know.” —Plato, Apology

Rest assured: recognizing the existence of uncertainty or confessing to lack knowledge on a given subject doesn’t make one’s position any weaker. One could do worse, after all, than take the lead from Socrates, who posited that awareness of one’s ignorance is a step along the path of learning.

Unfortunately, saying “I don’t know” doesn’t bring many readers to one’s website, newspaper column, or talk-show (for you youngsters, a “podcast”). Journalists, bloggers, tweeters, and other sports commentators make a name for themselves and develop a following by having opinions and being able to come up with them as quickly as the news cycle (or tennis calendar) demands. This is obviously not the place to diagnose the current condition of sports journalism. Rather, I want to point out that the need to say something—fast and frequently—can yield less than well-supported views and positions, which are often not adjusted, even if or when new information is acquired.

In terms of the Troicki case, needle phobia is the topic most commenters would have done well to acknowledge an insufficient grasp of—both in general and in terms of how it may have affected the events of that specific day. Many addressing the controversy simply ignored this aspect of the incident (which is certainly one, if not the best, way of dealing with the unfamiliar). But some writers took the opposite approach: not proceeding as if it didn’t exist or wasn’t worth discussing but acting all-too-certain about its relevance. As I’ve noted above, I think Troicki’s needle phobia is central to understanding the case; hence, it’s the focus of this “lesson.”

I’d already written this section when I ran across a recent piece that’s an example of the type of thing that set me off on a weeks-long research binge last November. As a result of that reading, I can state with confidence that Troicki’s needle phobia is a corroborated matter of fact. It’s a preexisting medical condition with both psychological and physiological symptoms—not a claim, not a suggestion, not a figment of his imagination, and not an “excuse” Viktor came up with one day because he was selected to submit a blood sample. It was accepted as such by both the IADT and the CAS on the basis of, among other “clear and convincing evidence,” the testimony of one of the French Tennis Federation’s chief medical officers, Dr. Bernard Montalvan (9I). In spite of this, numerous journalists felt free to dismiss it as a significant factor in the case—in the process, casting doubt not only on Troicki’s word (plus that of his coach, trainer, father, Davis Cup teammates, and friends/colleagues since childhood like Andrea Petković) but also, if indirectly, on that of the medical experts who submitted statements supporting it.

While this may seem, to some, an overly strong reaction to the skepticism, my view is that any journalist who suggests this part of “Troicki’s story was not corrobarated [sic] by the authorities” is open to numerous charges, including poor reading comprehension skills, sloppiness, laziness, irresponsibility, &/or bias. Frankly, unless you’re an experienced phlebotomist, psychologist, or someone familiar with current thinking on blood-injection-injury phobias, I don’t want to hear your musings on whether “having a little blood drawn was. . . going to harm Troicki if he was feeling a little under-the-weather.” In fact, I think it’d be best if no one heard such ill-informed speculations. I do my best in this section to help readers become more informed about the condition and consider the ways in which it may have influenced matters for both Troicki and the DCO that day.

3. Practice empathy.

As we have no immediate experience of what other men feel, we can form no idea of the manner in which they are affected, but by conceiving what we ourselves should feel in the like situation. Though our brother is upon the rack, as long as we ourselves are at our ease, our senses will never inform us of what he suffers. They never did, and never can, carry us beyond our own person, and it is by the imagination only that we can form any conception of what are his sensations. Neither can that faculty help us to this any other way, than by representing to us what would be our own, if we were in his case. It is the impressions of our own senses only, not those of his, which our imaginations copy. By the imagination we place ourselves in his situation, we conceive ourselves enduring all the same torments, we enter as it were into his body, and become in some measure the same person with him, and thence form some idea of his sensations, and even feel something which, though weaker in degree, is not altogether unlike them. His agonies, when they are thus brought home to ourselves, when we have thus adopted and made them our own, begin at last to affect us, and we then tremble and shudder at the thought of what he feels. For as to be in pain or distress of any kind excites the most excessive sorrow, so to conceive or to imagine that we are in it, excites some degree of the same emotion, in proportion to the vivacity or dulness of the conception.

—Adam Smith, The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759)

None of us—not members of the two tribunals, the tennis media, other players, or the author and readers of this piece—witnessed what happened in the Monte Carlo tournament DCS that day. Though we may have read Troicki’s brief version of events in the case documents or a handful of interviews, what we haven’t heard in vivid detail is what it feels like for him to go through a phobic episode. I suspect there are good reasons for this. For example, while the word “phobia” appears three times in the IADT (B9, D38, E46) and once in the CAS decision (3.8), Troicki himself doesn’t use that word in any of his quoted statements. This linguistic choice, which likely reflects “a tendency to downplay the fear and the significance it had in [his life],” aligns with what researchers have observed: “The very nature of the fear means it is not generally thought or talked about” (54, ii). Nevertheless, it’s unfortunate because it means we’re missing a key part of the story. But even in the absence of first-hand experience, observation, or abstract knowledge of something (what some might call “book learnin’”), we can still use our imaginations.

This section focuses on the difficulty of talking about mental-health issues in public—and thus, of combating both ignorance and stigma. These difficulties may very well be why we haven’t seen much discussion of Troicki’s condition in media reports on his case. However, recognizing that something’s unfamiliar or difficult isn’t a reason to avoid it. On the contrary, it’s a reason to pursue it by whatever means we have at our disposal. My effort is ongoing: I’ve reached out to the player’s representatives and hope to interview him once he’s settled back into the routine of week-in, week-out life on tour. But there’s no guarantee he’ll be willing to delve into the topic that I think most needs his insight. After this “lesson,” I hope more people will understand why Viktor might be reluctant to do so on the record.

It’s worth emphasizing from the outset that practicing empathy in this case doesn’t necessitate changing your position on whether the CAS decision was correct or Troicki’s suspension just. What I’m most trying to encourage readers to do, going forward, is imagine what needle-phobes (in general) and needle-phobic players (in particular) experience every time they’re faced with a blood-drawing procedure.

4. Acknowledge ambiguity & complexity.

Theory is good, but it doesn’t prevent things from existing. —Jean-Martin Charcot

The Judge does not make the law. It is people that make the law. Therefore if a law is unjust, and if the Judge judges according to the law, that is justice, even if it is not just. —Alan Paton, Cry, the Beloved Country (1948)

This section is dedicated to two groups, in particular: those, like Andy Murray, who seem to believe that following the rules is the (only or best) solution to the problems Troicki’s case presented; and those who haven’t to this point understood why some think the outcome of the CAS decision was unjust.

If you’re someone who has made categorical statements along the lines of “Read and respect the rules and everything is very simple,” “He should have taken the test,” “A player would only refuse to be tested if there was something to hide,” or “No excuses,” this section’s for you.